Welcome to the blog where you will find musings from around the vineyard and winery. News from the founder Andrew Hodson, a glimpse from the cellar and more.

ANDREW'S NEWSLETTER

VINIFICATION

EVENTS AT VERITAS

Browse by Category

Experience Veritas

Weddings at Veritas

Shop Wines

Have you got good taste?

September 4, 2020

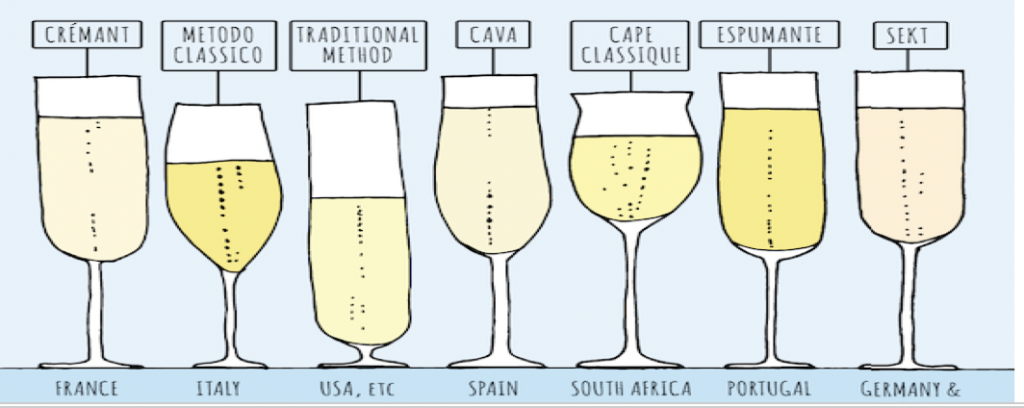

How to understand Sparkling Wine – the continuing saga. By Andrew Hodson of Veritas Vineyard and Winery

We saw last week that when you actually taste something, say for example a Veritas Mousseux the smell and taste combine to create what we call-”flavor.” The problem is there is no way that we can measure what it is that we are smelling.

Add to that that each one of us, as individuals has a different experience of what it is that we are tasting, our experience is “subjective.”

There is no “objective” way of describing smell, taste, and hence flavor.

In last weeks blog post I spent time describing how to organize our thinking when it comes to smells related to appreciating wine quality. Remember I emphasized how we can smell many more things than we can taste using that highly sensitive olfactory organ, the nose; by smelling carefully the smells can help predict the tastes.

This week I am going to focus on our ability to taste wine, understanding that taste has to involve both taste and smell – working together simultaneously to create flavor.

When it comes to tasting our abilities are much more limited to only five modalities:

Sweet

Sour

Salt

Bitter

Umami

The first four are familiar to most of us, but umami, often called the fifth taste, might require a word or two of explanation. Umami is the flavor of “savory” and here we run into the very problem of using words to describe smells, tastes and flavors.

We have to say it smells or tastes LIKE something we are using comparative terms in English those comparative terms are called similes. So umami is like the smell/taste/ flavor of “savory”-whatever that is.

Umami –noun

a category of taste in food (besides sweet, sour, salt, and bitter), corresponding to the flavor of glutamates, especially monosodium glutamate.

The word “Umami” is a loanword from Japanese, translated as “pleasant savory taste” -the flavor of broths and cooked meats. Be wary though of monosodium glutamate – MSG a food additive that is almost universal – the sodium part of monosodium makes it taste more like salt than it does of savory. The thing to remember is the word GLUTAMATE – is the salt of an amino acid – glutamic acid that is the core component of umami that gives savory flavor.

Now there is a body of wisdom that would have you believe that the tongue, the organ most dedicated to taste has certain areas that are more sensitive to certain tastes than others.

It turns out that when subject to more rigorous neuroscientific study these maps like so many things in “popular” science are gross oversimplifications.

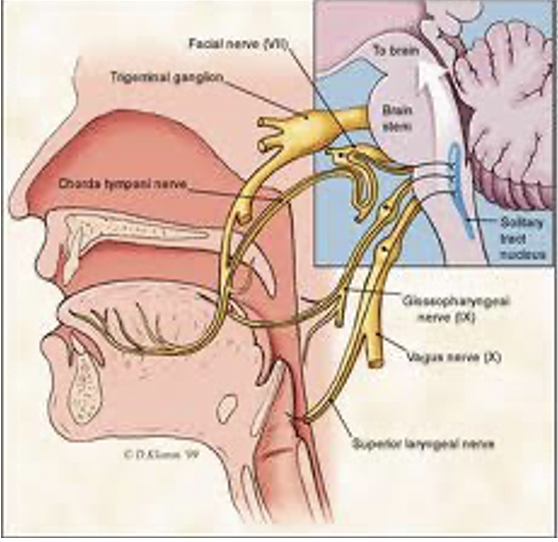

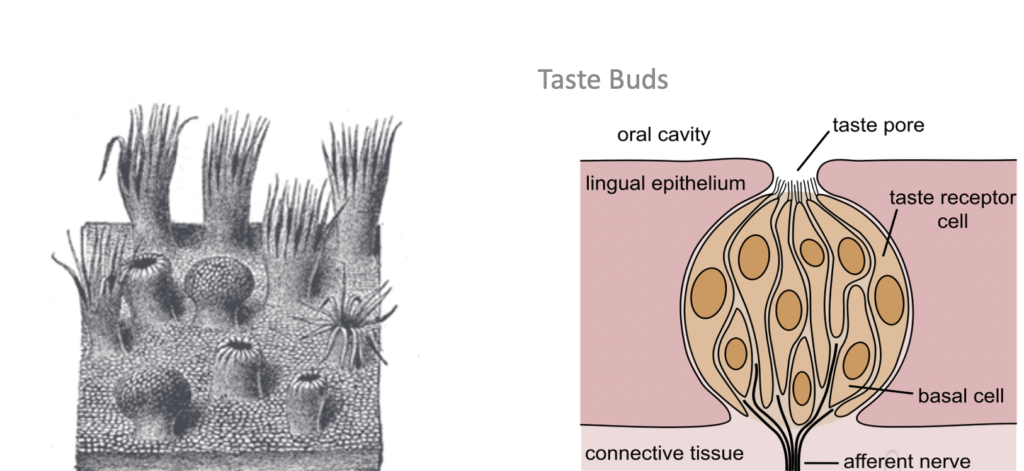

When it comes to tasting the skin covering the tongue – the epithelium has developed a number of specialized “end organs” or receptors. Those receptors convert chemical interactions with flavor compounds to initiate nerve impulses that go to specialized areas of the brain to create an experience that we interpret as the sensation of taste.

It has been shown that there are certain individuals who have been endowed with particularly high numbers of these receptors on their tongues and as a group have been designated as “supertasters” but you do not have to be a supertaster to enjoy the joys of wine.

Just as we organized our thinking in appreciating the categories of smells in a wine we can do a similar exercise in tasting a wine. The designation of primary, secondary and tertiary aromas as I described last week holds true is designating tastes. However, tasting and describing the properties of a wine do not only involve smell, taste and flavor they involve other component properties of wine particularly the sense of touch.

We literally feel the wine on the tongue and palate what is called sensory information that gives us the ability to appreciate feelings of texture and viscosity, the sensory input that allows us to appreciate the “body” of the wine. And in this case we have to use a different set of similes that act as adjectives compare the wine to things we feel so we describe a good wine as having silky or velvety tannins a not so good wine as rough or harsh all descriptors of what we feel.

The key to being able to use what seem to be a multiplicity of descriptive terms is to have a

FRAMEWORK , a structure that you use the same way every time you taste a wine. Think of it as a checklist, a way of ensuring that when you taste you include everything there is to include.

So my aim is to go through the construction of that framework piece by piece a pattern that has been established by the Wine and Spirits Education Trust (WSET) a non profit organization that originated in the UK with the express purpose of improving the means of communication about wine that serves the purpose of the novice beginner to the master of wine the framework is the same throughout.

The WSET methodology has withstood the tests of time as the most effective method available like everything the method is not perfect but it is the most widely accepted method in the wine world.

As we taste we compartmentalize our thinking into the consideration of each one of these framework properties each time we taste and every time we taste this method is designed for us to witness everything the wine has to offer.

The tasting framework is made up by considering the following properties in a given wine

Sweetness

Acid

Tannin

Alcohol

Body

Flavor intensity

Flavor character

Finish

In this piece I am going to focus on the first major property of a wine and that is the degree of sweetness.

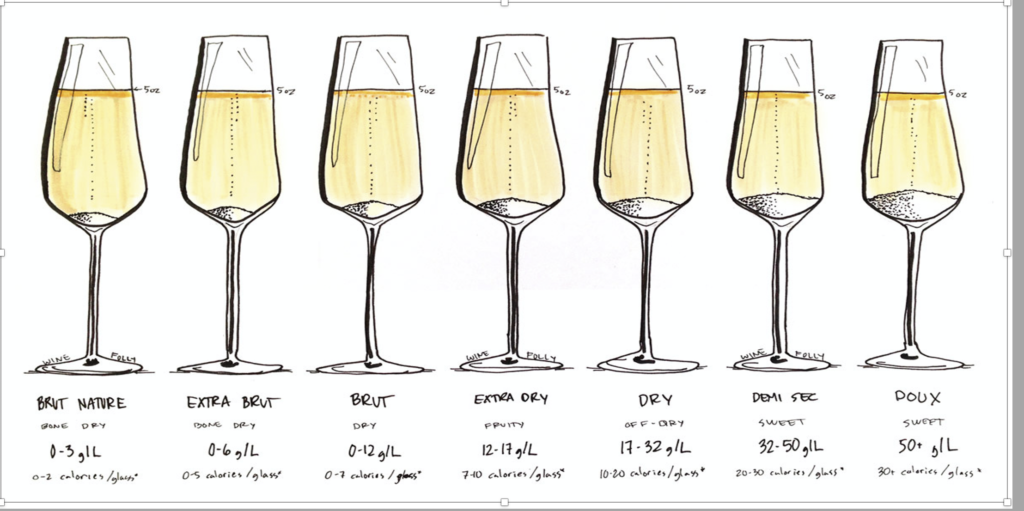

Sweetness is primary and is fundamental in our thinking about wine. In the global picture most wines are dry, that means that all the natural sugars from the grapes have been converted to alcohol, there is no sugar left i.e. no residual sugar. There is no arena where sweetness is so key as in the arena of sparkling wine. In the good old days sparkling wines were much sweeter than present day, sugar was a marker of opulence and if it was not sweet it was crude or as the French would say “brut.”

As I have emphasized throughout we are all different in our abilities to taste things and one of the easiest to demonstrate is how we all differ when it comes to tasting sugar.

For most people there is a threshold, a level above which most people can taste a sugar solution and that level is 0.75 % that 0.75gms of sugar in 100 ccs . Just to give you an idea. A teaspoon of sugar is roughly 5.00gms and if you put a teaspoon of sugar in a cup that would be the same as 2.00gms in 100 ccs.

In sparkling wine a Brut wine is generally considered dry with a concentration of less than 1.2 gms per 100 ccs or 1.2% most people can detect some degree of sweetness at that level.The way sparkling wines are described harkens back to French tradition. So the most recent fashion in the sparkling wine world is to get drier and drier. “Brut Nature” is about as dry as you can get 0- 0.3%, Extra Brut is 0.6% and Brut is 1.2%. Now you would think that a wine called “Extra Dry” would have less sugar than a Brut but it doesn’t. The way to make sense of it all is if you recall I explained that in the good old days sparkling wine was typically a lot sweeter so a wine with 1.7- 3.2 % sugar was considered “dry” a wine with 3.2- 5.0% sugar was called “Demi Sec” and finally to be considered sweet or in French “Doux” it had to contain more than 5.00% sugar.

Now no discussion about sugar would be complete without a discussion of acidity the two are inextricably linked and that will be the subject in the next blog – How sugar and acid balance each other and why that understanding is crucial in sparkling wine. As the series continues I will continue to address each component of our structural framework including tannins, alcohol, flavor intensity flavor character and finish up with the finish of the wine.

Lots of fun to come as we go through the witnessing of wine before we come to the point when we have to decide is this wine really worth the price I paid for it?

Watch this clip of Emily talking about our Rosé sparkling wine that we have named Mousseux and yes you guessed it is on special this week so check it out on our website

Keep tuned for next week‘s stunning account of how to understand sparkling wine.

Andrew Hodson

A most enjoyable and informative read. Thank you!